Mansu is hiding! Hiding and worrying about the “missiles”, the “soldiers”, their “colossal firepower”, and the “two or three hundred million dollars” that they are willing to spend just to kill him. Burrowing his way into the undergrowth of Mt. Hyangmi, Mansu thinks aloud about the disproportionate punishment coming his way, the army below him readying their weapons, and his ancestors… all of them!

Just as he has been reminded of throughout his young life, Mansu is now always looking to talk-up his pedigree. Three generations ago the mythologised noble bandit Hong Gil-dong stalked the Choson dynasty with the same blood in his veins. Before him, there was Tangun, offspring of a bear and god, ruler of the peninsula, and the mythologised first Korean.

With such royalty at his back, Mansu is chastising himself and trying to hush-away all that fear. The troops are American – the liberators and new foreign power to be tip-toed around. And that royalty, that legacy arching back to supposedly kind thieves and sacrificed deities, is Korean all the way down. Stories of appropriate hardship, injustice, and overdue righteousness – but more importantly, an inheritance so loose and deliberately empty that everyone has a claim, if they desire it.

Mansu spends most of his final minutes before us thinking about his final seconds: whether his body will be “broken into pieces”, or “explode together” with the mountain, or become reduced to “dust… blowing in the wind”. He thinks of Tangun and Gil-dong and whether, with such royal blood, he might be immortal, in a way: “will I really die because of that?”

He also doubts himself, doubts whether he is deserving of his genes and the label Korean – shifting fast between imagining himself as protected by heaven, and that of being “threw up… by the devil”, unrecognisable as a “human being”, “dirt, certainly dirt”. A man who “should die in vain without ever blossoming” having lived only a “ridiculous fable of a life, subsisting mainly on the urine and shit dropped by foreigners”.

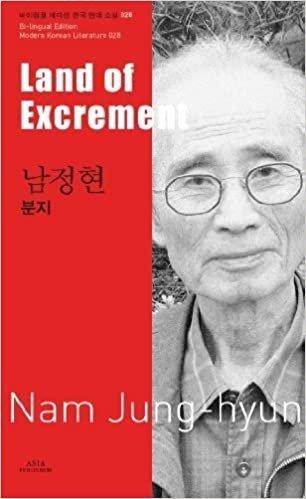

It is here that Land of Excrement finds itself as a novel. No one will ever pick up this book and fall in love with the prose, the character development, the pacing of the narrative… This is an unpolished and unconcealed political statement about post-colonial Korea and its happy worship of a new foreign power to replace the old.

It is a story of national inferiority hiding behind a blanket of false pride and grandeur. Of streets and houses and schools and apartment complexes and jobs and shopping centres and parks and cafes and restaurants and of friendships and families and marriages and love affairs and chats about the weather, where people think themselves – at every turn – to be lions, while shuffling around in small steps, their eyes on the ground, and their shoulders slumped in subservient resignation.

Land of Excrement was the first novel to be dragged through the courts of an independent Korea, and its author, Nam Jung-hyun, the first writer to be arrested, indicted, convicted and imprisoned for putting pen to paper. All this, not for being anti-Korean, nor anti-government, but rather anti-American!

When it all kicks off we are on a twenty minute countdown to launch, “to ear-splitting noises”, and to death; and with Mansu contemplating sexual violence! The rape of his mother, his sister becoming the mistress of an American soldier, Master Sergeant Speed, and his own sexual assault of Mrs. Speed through near-childish curiosity:

I politely told her that I had to ask her a favour in the name of the Republic of Korea with its brilliant five-thousand year history… She smiled and asked me what that favour would be…

“I’m sorry, but you have to briefly take off your clothes.”

The full symbolism of this naïve lead-in to atrocity is open for interpretation. But the shallow symbolism is obvious, blunt and unimaginative – the work of a teacher trying to indoctrinate rather than that of a novelist trying to produce art, beauty or truth. And the juvenile simplicity of our main character continues after the attack:

[Mrs Speed] suddenly got up and frantically ran down the mountain, crying sharply,

“Help me! Help me!”

Why was she acting that [sic]? Running away with her dishevelled hair and torn clothes,

As Mansu watches on like a bemused student on the first day of school, we are supposed to nod our heads in agreement, as if everything was suddenly clear and obvious: decades of weakness and attachment has warped the Korean mind all the way back to childhood. But even children still have a sense of things, and can more often than not sniff-out right from wrong, good from evil. So where is the good to be found here? What is the message that Nam wants his readers to sit awake at night thinking about? The purifying value of revenge (even if only accidental) and the virus-like quality of depredation.

Either way, Mansu quickly finds himself on the run from Mr. Speed and his troops, and scrambling toward some brief salvation in the mountainside. It’s there, hiding, scared, and wishing to see his mother and sister one last time, that Mansu also begins retrofitting his crime to his adult frame, comparing himself to Jesus and humming about a newly discovered “very deep grudge”.

There was something of a controversy around the original publication of Land of Excrement, with Nam upset and claiming that it was done without his permission. The line which the establishments of Korean literature and Korean culture has settled-on is that this was all about Nam trying to assuage the censors and avoid prison.

Perhaps now we should think differently, or at least ask the question: with such rambling and raw prose, with such a subconscious-like flow to the story, and with such a disconnected and confused moral burn, maybe, just maybe, Nam Jung-hyun protested the publication for a literary reason? Maybe he didn’t want an experimental first draft pumped-out to the world and presented as the finished article.

His twenty minutes are up, and so Mansu makes one last desperate grasp for inspiration, for a legacy, and for national rebirth (in characteristically unmoored and probationary language):

Only ten seconds to go. Right. Now I’ll make a splendid new flag by tearing up my Taegeuk-patterned [Korean flag] undershirt. Then I’ll get on a cloud and cross the ocean. I’m planning to carefully stick this rapturous flag into the lustrous navels of women with milky skin, women lying down on that great continent, women that I appreciate. Believe me, Mother. I’m not lying. You still cannot believe me, trembling. What a pity! Look, now! Please look at these bulging eyes of mine! Well, do I look like I’ll die that easily? Ha-ha-ha!