In conversation with Susan Blackmore

We human beings are difficult little animals. In some obvious enough ways we are just like all the other species out there: fragile sacks of genes and cells and blood and lungs and brains and hearts; eating, fighting, hunting, procreating, aging, and dying. But in other – still obvious ways – we are of a different kind: talking, writing, reading, building, and theorising our way to space travel and nuclear power and quantum mechanics and cures for disease and robotics and pocket computers and the internet.

So what is it that makes us so special, and allows us to achieve such unbelievable – magic-like – progress from such a mundane biological starting point? To what do we owe our intelligence, our consciousness, and our comfortable lives? Here we have never been short of a theory or two, and never close to a satisfactory one… until now! And just like with its cousin-theory – Darwinian natural selection – this great new idea bounces between complexity and simplicity: easy enough to understand at a glance, hard to get your head around in its detail, and so profoundly unassuming that it often feels incomplete; leaving us dumbfounded as to how this small attribute could have such an enormous reach, considering all that has been done in its wake.

“What makes us different” writes Susan Blackmore, “is our ability to imitate”. It is an ability that we share in primitive ways with other animals as well, but they don’t take to it with the vigour and intuition that we do. Try waving at your cat, and see what happens. Keep on waving for hours or days or months, and the cat is never going to wave back. You can train the cat with rewards or affection or punishment to do certain things, but you cannot teach it by demonstrating the behaviour yourself.

Take an impossibly foreign human being though, someone with no understanding or experience of a waving hand, and after seeing you do it in his direction a couple of times, he will instinctively begin to copy you. He will then also, very quickly, make the connection between the gesture and its meaning. He will then wave at other people, they will wave back, and the imitation has a life of its own. “When you imitate someone else, something is passed on”. That something is a meme… and it explains who we are as a species.

The big brain. So many of the traditional answers to our previous question – what makes us different from other animals? – are quick references to the brains we have. So much so that the question is often asked differently: why do we have such enormous brains? And before you answer, make sure that you are not making one of two mistakes. 1. Slipping into a circular argument of the kind: we have big brains because they make us more intelligent, we became intelligent because it helps us to survive, and so we developed big brains to help us survive. Nothing is being answered here other than what we already know: our brains are big and our brains are useful. 2. Forgetting that biological evolution moves in small increments through random mutation, and that it is not indulgent. That something may be beneficial on paper does not mean that it will be selected for by nature, nor that each small, incremental change on the path there carries enough individual survival benefits to make an evolutionary difference.

Take primitive hunter-gatherer societies – our ancestors – and people whose survival rested upon understanding the world around them: seasons, migration patterns, basic tools, alternative food sources, cooperation… Having a larger brain would certainly have helped them with this, but did it have to be as large as the ones we have? The range of things they needed to do in order to endure and thrive was limited, and with each increase in brain size comes an intolerably large increase in survival-related problems.

Human babies are hopeless little creatures. That big brain comes with a big head, and that big head is a tremendous hassle. With a close ratio between pelvis and skull, childbirth is an unhealthy ordeal, where some mothers – and babies – don’t survive the birth; even then, human babies are born extremely premature, soft-skulled and unable to fend for themselves, becoming a heavy burden upon the species; and the brain itself does not sleep or rest like our other muscles, so it is always burning energy, needing a disproportionate amount of calories to keep it going. Expensive to build and expensive to maintain, we have a problem to solve here: “a smaller brain would certainly save a lot of energy, and evolution does not waste energy for no reason.”

So there must have been a selection pressure for our bulbous brains, something that outweighed the trouble they cause. It also happened fast (in evolutionary terms). Somewhere around 2.5 million years ago, with our hominid ancestors, our brains began to grow dramatically into what we have today. And so the theories often begin with the archaeological record, and with toolmaking: the pressure first comes from the environment and the animals within it, and then our need to outwit prey, to evade predators, to mould the landscape in small ways; technology was needed, and for this we needed bigger brains. But surely we didn’t need ones as big and costly as what evolved – a much smaller, less cumbersome brain would still be able to make tools and still be able to form hunting strategies, as we can see in limited ways today in other species.

If it wasn’t toolmaking that made the difference, perhaps it was a matter of discovery, spatial awareness, and map (cognitive) building. Foraging for food is no easy business, and environments are unpredictable, dangerous places to wander about aimlessly. Here a bigger brained ancestor of ours would have had a competitive advantage by storing more locations of food in his mind, more dangerous places that ought to be avoided, and more landmarks for quicker navigation. The trouble is – again – that big brain of ours is overkill. Animals that make complex cognitive maps do also show an increase in brain structure, but not in overall size. Rats and squirrels make complex maps of their environments in order to survive, and yet they do so with fairly small brains.

How about consciousness then? Imagine an early ancestor of ours who has suddenly developed the ability to look into his own mind and contemplate his own existence. He is the first of the species with this ability, and it comes with an enormous benefit. By analysing his own mind and his own behaviour, he is able to build primitive theories about the other members of his tribe: who will be aggressive in what circumstances, how emotions of sadness or happiness or surprise or anger or confusion will affect people’s behaviour, and how to build firmer relationships with allies and sexual partners. All he has to do is think how he would respond in the same circumstances.

The problem with the consciousness answer though is fairly obvious. First, it is hard to pin down whether consciousness is an evolved – selected for – function, or an epiphenomenon of another function like language or intelligence or attention. Second, it is incredibly tenuous to say that consciousness is a uniquely human quality, and that it provided such a fierce advantage as to make large brains – with all their downsides – necessary. Finally, and most critically, we still don’t know what consciousness is, and “you cannot solve one mystery by invoking another.”

The Machiavellian Intelligence hypothesis is the most fun. Forget any notions of improved cooperation, compassion, understanding, or relationship-building, instead what our big brains evolved to do was to con, outwit, and betray our fellow members of the tribe. Social life has certain rules – often unspoken – that guide how we should act, in what circumstances, to whom, and what should be reciprocated. This is all nice enough, but anyone willing to break these rules has a clear advantage over the rest, who don’t. Especially if those rules are broken in cunning, devious ways that hide your indiscretions, diminish or destroy your enemies, and craftily propel you upward in terms of status, power, resources, and survival. And all this scheming requires a lot of brain power.

This takes the social function of the brain to a whole new level. Arms races are not foreign to biology, but if inter-species competition is the endgame of our big brains, then it seems to have dramatically overshot its landing. Being larger, stronger, or faster are all ways of outcompeting your neighbour for food, or shelter or safety or sexual partners that are not nearly as biologically expensive as having enlarged brains. Why the pressure was heavily set upon social skills still needs explaining, as does the growing complexity of social life. Besides, is it really acceptable to say that our ability to do mathematics, paint cathedrals, build computers, or understand the universe, comes down to our improved social skills? This seems like a jump. It certainly leaves more questions than it answers.

Instead maybe, just maybe, the “turning point in our evolutionary history was when we began to imitate each other”. But before we get to that, we must talk about language and its origins.

One of those incomplete thoughts about the evolution of our big brains is about the fact that we talk, a lot. We just don’t shut up! Think of any common-enough human activity, and then think what it is mostly about. We meet friends for lunch, have drinks after work, settle-down to watch a football game, and it is all – largely – a pretext for having a conversation. Perhaps it is easier to think of it this way: think of a group of people – two, three, four, five, it doesn’t matter – sitting together somewhere, anywhere. Are they talking, or are they happy in the “companionable silence”?

Language too comes at a high cost – “if you have ever been very ill you will know how exhausting it is to speak” – and so it takes some explaining; and for many socio-biologists it is connected to our big brains. Communication matters. It helps us to form social bonds, to pass on useful information, to cooperate more effectively, and it helps us to build culture. The more detailed and precise the communication, the more effective it will be in achieving these things; and all those extra layers of nuance and complexity require more brain power, and so the two evolve together. But because they do, the same hurdle catches both. If it is all about competitive advantage, then why has language – as with our brain size – got so out of control? If we just talked a little less, we would save energy, and by using less energy than our chatty neighbours, it would be us – and not them – who had the competitive advantage. Evolution didn’t produce creatures who are capable of complex language, it produced “creatures that talk whenever they get the chance”.

So much of Blackmore’s work here is an attack on this type of socio-biology, these incomplete theories that push the problem of our intellectual evolution someplace else, and then announce loudly that because it moved it is solved. The mistake is always of the same kind: trying to explain our extraordinary – and unique – development in terms of genetic advantage. It is an understandable mistake… but still wrong!

So back to that quote from Blackmore – “When you imitate someone else, something is passed on” – and the importance of imitation. Look around yourself, and just like all those people before Charles Darwin, you are likely to not notice the most extraordinary aspect of our reality; oblivious to the driver of all life, to all evolution, to all knowledge, to everything that matters about being the creatures we are. The trouble comes about largely because we have become so damn good at it. Despite how extremely rare it is (drawing the hard line between ourselves and the animals), all that imitation and copying and replication tends to pass us by unnoticed – so successful and so constant, it has become almost boring.

Genes. Evolution is helpfully thought of as competition; competition between replicators. It is less helpfully thought of as something that happens for the “good of the species”. The mistake is thinking of the organism as a whole, that evolution cares about the survival of the animal in question. It doesn’t! Biological evolution happens at the level of individual genes, and those genes have only one – deeply selfish – purpose (not the right word because genes don’t have intentions in the human sense): to replicate. To be passed on to the next generation.

It is tempting to look at the development of a new wing or a larger body or better camouflage or any given Gene X, as working to improve its host’s chances of survival. But genes don’t have foresight. They don’t have desires of any kind. They simply become what they are through mutation, and are either successfully passed-on through sexual reproduction, or not. The ones that are not, die out, and the ones that do live on, reproducing again and again, until they too die out through changes in the environment or competition from other genes. The crossover that trips us up, and has people using the language of intentions, desires, wills, hopes and purposes is the connection between passengers and their hosts – “between ‘replicators’ and their ‘vehicles’”. It just so happens that if we die, our genes die with us. So we have that pitch in common: the human vehicle wanting to live-on for a variety of reasons, the individual genes wanting (again not the right word) the human vehicle to live-on as well, or at least long enough to have sex, and so allowing the genes to replicate in new vehicles (offspring).

In this, our genes are more like indifferent and greedy parasites (getting as much as they can, as quickly as they can), than members of a team pulling in the same direction. The errors of language in the previous few paragraphs tell a story in itself: just how hard it is to think about evolution, and how hard it is to talk about it accurately, despite it otherwise making intuitive sense. And so it can’t be stressed enough, what it comes down to is replication, replication, replication. Or with a little more elegance, and in the words of evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins: “all life evolves by the differential survival of replicating entities”.

Memes. Look around yourself now, go outside and really look at your fellow human beings. See if you can break through that background noise of normality. See if you can notice the next step in replication, the non-biological kind. Look at the clothes people wear, the music they listen to, the cars they drive, the food they eat, the gestures they make, the catch-phrases and turns of language they use, the hairstyles they sport, the movies they watch, the books they read, the ideas they profess, the tools and the technology they use… Once you slow down enough, and spend the time to re-notice the things you take for granted, you will see these habits and preferences and desires and fashions and fears for what they are, and what they are doing. Jumping from host to host, from brain to brain, they have a life of their own, and a goal of their own: replication!

This is the world of memes, and it is indistinguishable from the world of human beings. Each and every meme, just like each and every gene, evolved individually and in groups (memeplexes or genomes), with different and connected histories. They are unique, they evolved, and they make us do things. They make us speak in certain tones with certain words, drink Coke or Pepsi, wear a green shirt rather than a blue one, and eat pizza rather than a hamburger. What they all have in common is you! “Each of them” writes Blackmore, “is using your behaviour to get itself copied.”

You heard that right! Your food choices, clothing choices, language and thoughts, are using you, not the other way around (well at least not in the same malicious way). The next great technological invention is likely to spread around the world because it is useful, improves lives, and so that makes it something worth getting a copy of. The next breakthrough in science might spread too, because it has truth on its side and makes the building of new technology possible, but it is likely to spread with less fecundity because it is harder to understand, and has fewer immediate uses for the average person. A catchy tune or song on the other hand – take Happy Birthday to You as an example – might ripple effortlessly around the world, across language barriers, copying itself again and again, to the point where just hearing the title, or thinking about a birthday party, brings it faithfully back to life in your head.

As you hum that tune and remember those lyrics, ask yourself the hard question: “where did that come from?” It is firmly locked away in your memory, just as it is locked away within the minds of millions of other people, and yet its beginnings, its history, its origin, doesn’t matter. What matters is how it came to you, why it stuck when so many other tunes didn’t, and what it makes you do (sing it at birthday celebrations). What is the cause of all that extraordinary imitation? Something under the surface of the behaviour itself (remember there is a difference between replicators and vehicles) is lodging itself within the minds of its hosts (me and you) – “some kind of information, some kind of instruction” – and causing itself to replicate when it comes into connection with other hosts. This something is the meme!

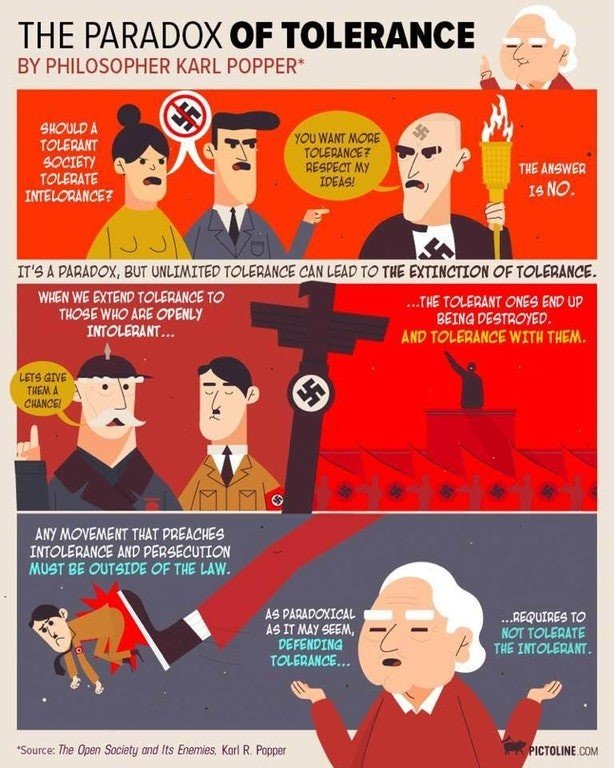

Some of these memes are helpful to us, like new technology; some are entertaining, like songs; and some can be positively harmful, like pyramid schemes, financial frauds, false medical cures, unhealthy body images, social media addictions, dangerous ideologies or bigotries. Memes are indiscriminate and uncaring, like genes they are selfish and are only interested (the wrong word once again) in spreading as widely as possible. It is a challenging idea – striking “at our deepest assumptions about who we are and why we are here” – but one that satisfies the Popperian criteria for being a true theory: 1. Has testable predictions, and survive those tests, 2. Solves problems and explains things better than the rival theories.

Some memes succeed, whereas others fail, for obvious enough reasons. We all have limited processing capacity in our brains, as well as limited storage capacity. And so, no matter how well adapted a new meme is to our psychology, or how well-geared it is to being imitated and selected, it is always going to struggle in such a competitive landscape. The best ones are the most evolved ones, the memes that arrive in our minds through countless variations and combinations of old memes; the errors and baggage slowly carved away, with gradual improvement upon gradual improvement adding-up to make the meme a ruthlessly efficient copier.

But we human beings are fallible, we make mistakes, constantly, so all this combination and selection is a tricky business. Especially if everything hinges upon our passing on something we hear or see – a song or a story or a theory or a fashion trend – faithfully enough that it can then be passed on by others, and not diminished with each replication. So the most successful memes have something about them: depth. A joke is a great example of a meme with this quality. When a joke is told for a second time, and then a third time, and then a millionth, it is rarely ever told the same way; but the joke is unmistakably replicating, and so it must be replicating for a good reason.

That reason is that the joke is humorous, it makes people laugh, and that makes people happy, which then makes them want to share the joke. The exact format of the words don’t matter, what matters is the underlying structure or pacing or punchline that makes it funny. Get your hands on a joke, change the words completely, even change the setting from a jungle to a café for example, and the joke might still work if you are clever enough with how you adapt it. But then forget the punchline or a core feature that makes the punchline work, and then no one will laugh, and the meme will die. The most important thing about the meme is not the raw details, but the meaning behind those details.

The way a joke of any kind gets into your mind, is the way in which everything else does. They might be individual memes, surviving alone and replicating on their own weight, or giant clusters of memes, all bound together, feeding off each other, surviving together, replicating together. These, for lack of a better word, are memeplexes, or as Dawkins calls them with some helpful imagery, “viruses of the mind”. Think cults, religions and other dangerous ideologies, and you have a reasonable picture of what a memeplex looks like, though they don’t have to be necessarily pernicious. Add enough memes together, and enough memeplexes, and what you have is a complete human mind.

But these memes have another evolved talent, something that makes their lives a little easier. They don’t just find a place within a given mind, but once there they begin renovating, actually working to “restructure a human brain” according to Daniel Dennett, “in order to make it a better habitat for memes.” Take farming as an example: contrary to what we tend to think, it did not improve the lives of those early adopters, it did not reduce disease, and most counterintuitively it did not increase the quality of nutrition. When people like Colin Tudge look at the skeletons of the earliest farming communities from Egypt, all that looks back is “utter misery”; starvation, illness, deformed bones from the excess workloads, and everyone dying long before their thirtieth birthdays. So why did farming catch on?

The answer is fairly simple, and connects the two mysteries: those farmers’ lives didn’t improve for the exact same reason that farming became so popular! The more food they managed to produce, the more children they were able to have, and with more mouths to feed there was more work to do, more food to produce, more land to be bought or seized, and ever more children to feed; children who would grow up to be farmers, and who would run through the same cycle. Then, with less and less land available for their traditional way of life, hunter gatherers would have few choices but to drop their spears and take up plows. Step back and what does this look like: replication, replication, replication!

Farming took off in the way it did, and spread rapidly across the globe, not because it made people happier, healthier, or more comfortable, but because it was a good meme; well-adapted to its human hosts. With a “meme’s eye view”, the world looks a very different place. Instead of asking how new ideas or technologies benefit human beings, we should be asking “how they benefit themselves.” The subjective experiences of the people whom these memes are running through, and the emotions they feel, are a part of a much more complex process, triggering some things to be imitated, and others to not be. At this point, our memes are well and truly off the leash, living a “life of their own”, causing themselves to be evermore replicated, and manipulating our behaviour to get this done.

Sure, genes are a prerequisite for memes – the creation of brains that are capable of imitation was necessary before the first meme could ever be formed. But once that happened, once brains of that kind evolved, all the popular talk of biological advantage, and of evolutionary psychology, almost entirely misses the point. Memes, once born, are independent of their genetic origins, they are a second replicator, acting entirely in their own interests. Sometimes those interests coincide with biological and psychological health, and sometimes they can be positively harmful. So we better begin to understand them in as much detail as possible.

To do this requires a return to the meme’s eye view. Memes look at the world – and at us – in a very singular way: “opportunities for replication”. Every time we speak, we produce memes. The trouble is that most of these die immediately, never finding a new host, and never being spoken again by ourselves. If one of those memes manages to get onto a radio broadcast, a television program, or into the pages of a book, it has dramatically increased its chances of replication, and so it has a competitive advantage. Our brains and our minds and our behaviours are nothing more than opportunities from the meme’s eye view.

Think of what you are reading now, the words on this page. It started with a thought in the mind of Richard Dawkins. That thought caused Dawkins to write a brief aside – 15 pages – in his book The Selfish Gene. Which was then read by Susan Blackmore, and it caused her to flesh out the theory over 250 pages in her book The Meme Machine. The physicist David Deutsch read that book, and added some missing details to the theory in his own book The Beginning of Infinity. I read Deutsch’s book, which caused me to go back and read Blackmore’s, which caused me to interview her and publish our discussion, which caused me to write the words you are currently reading. The theory of memes is itself a meme, though only a mildly successful one.

It might be easier to think of this in terms of the types of brains and minds we have, and the changes that memes have made to them. Try for a moment a little self-experiment: try to stop thinking! Stick at it for more than a few seconds and some thought or another will pop into your mind. Push that thought away, try again, and you will likely only last another second or two before you are bombarded by thought after thought. The whole practice of meditation is built around being able to calm our ever thinking minds and give us a few more moments of peace.

All this thinking is extremely stressful, as we worry about the glance someone has given us, whether we turned off the lights before leaving the house, what we should eat for dinner, how we should dress for that business meeting tomorrow. Try as we may, emptying the mind is a nearly impossible achievement; and yet one that would be very beneficial to all of us from time to time. All that thinking and worrying drives unnecessary stress and anxiety and depression into our lives. What is obvious, if you pay enough attention to it – perhaps through meditation – is that we are not in control of what we think; thoughts just happen, and we cannot turn them off.

All that thinking also requires a lot of energy and calories, so what on earth is it all about? Why do our minds do this to us? The answer to this question – and so many others like it – goes back to the same starting point: you have to think in terms of brains which are capable of imitation, and “in terms of replicators trying to get copied.” A meme that isn’t paid any attention is doomed, slipping silently out of its hosts’ minds. Memes that capture and dominate our attention on the other hand, are much more likely to get acted upon and then passed-on to other minds who will do the same. So memes evolve to capture more and more of our attention over time and with that, the reason you can’t stop thinking begins to make sense: “millions of memes are competing for the space in ‘my’ brain.”

With far more thoughts (memes) competing for the same limited space in our minds, Blackmore likes to think of it in terms of a vegetable garden. You can try to clear the soil, and plant the seeds you want, but before long the green tips of weeds will appear. Wait a little longer and there will be more. All the clearing and pruning and de-weeding of the mind (through practices like meditation) have an effect, but the process continues: weeds fighting for sunlight and water and nutrients, competing for space against other weeds and against the vegetables you actually want to grow. Memes are “tools for thinking” and so they thrive most successfully in hosts that think a lot.

These memes also have another sinister trick up their sleeves. Not content with the brains which evolution gave us (and so gave them) our memes target our genes. They change our behaviour, and so they also change the genetic grounding for why we have sex, when we do it, what we consider sexually desirable, and how we raise children. Once the prisoners of genes, when memes arrive we are sprung from that prison, and our genes take our place behind the bars. By changing certain behaviours of ours and by working towards making their home (our minds) more hospitable, our memes turn us toward their own light.

Memes want to spread, it is all they want! So they prefer to find themselves in a human-host that is genetically well-adapted to this purpose: be it people who are inclined to religiously follow trends, people who are naturally more charismatic and so capable of influencing others, or people with better focus – and more attention to detail – who are therefore better able to accurately copy and share memes. For this, they need certain things from their hosts (us): more proficient brains with more memory capacity and processing power, better sensory organs to perceive memes and then copy them faithfully, and certain personality traits conducive to replication and imitation, like the ones mentioned above. And they can get these things done in the way they get everything done: by changing our behaviour. In this case our sexual behaviour.

“The sale of sex in modern society is not about spreading genes”, how could it be, with all its anti-evolutionary (biological evolution that is) qualities? Rather, “sex has been taken over by the memes”, and with it the rest of our biology.

So after a long detour around the world of memes, back to those big brains we first puzzled over, and back to a better answer. The high point in our evolution, when everything began to change for us, was when we started to imitate each other. Before this, biological evolution inched its way forward, and the type of rapid and unusual change that we see with the development of our outsized brains, was seemingly impossible. The necessary selection pressures just weren’t there, and our best socio-biological theories didn’t work as explanations. But with imitation, a second replicator (other than the genetic one) is let loose, changing the environment, changing our behaviour, and changing which genes are selected for; radically altering our evolutionary path.

The exact moment this happened is lost to history, but unlike all those socio-biological theories, the “selective (genetic) advantage of imitation is no mystery.” If your neighbour has developed some sort of good trick, something useful, or valuable, it is clearly beneficial to yourself to be able to copy him. Running things back again to our hunter-gatherer past, perhaps this neighbour has discovered a new way to find food, a new mechanism for building shelter, or a new skill for fighting. The people who saw this and ignored it, choosing instead to continue along seeking food or other improvements as if nothing had happened to the man next door, paid a price. The people who noticed these small jumps in progress, and decided to copy them, learned valuable skills, new knowledge, and were better-off for it.

But imitation is no easy thing. It just seems easy to us now because our memes have been running the show for so long, and our genes are now so fine-tuned to memetic purposes. There are three requirements, or skills: 1. Deciding who or what to imitate, which is no easy thing. 2. Decoding information from complex behaviours, technology, theories, and transforming that into your own behaviours, technology, theories. 3. Accurately matching bodily actions. Very basic versions of all these skills can be found in primates today, and five million years ago our ancestors had the same latent abilities.

Two and a half million years ago, the first stone tools were made and we had our first obvious signs of imitation. Without rehashing all the mistaken ways that big brains have been thought to evolve, memetic theory has the Popperian benefit of being able to explain the phenomenon (big brains) as well as the empirical content of all these other theories. All those cooperative and bonding social skills, the cunning and the deception of Machiavellian intelligence, the navigation and pathfinding of cognitive map building, the leaps forward in survival that come from tool making, and all the spin-off benefits of consciousness, are explainable by a single development. A threshold, that when crossed by our ancestors, transformed so much, and took on such a life of its own, that it became hard to even recognise through the enormous dust cloud of change and success.

The first step is what Blackmore calls “selection for imitation”. And it’s the simplest. Somewhere in our evolutionary mess, a genetic variation for imitation happened. The people with this variation had an immediate advantage, copying the best primitive tool makers (to use that as an example). Building better spears, better baskets, better huts, they thrived and so the gene spread. The next step is where things become really interesting: “selection for imitating the imitators”. When everything around you is changing, and that change is speeding up due to imitation, it is not always so easy to know what to imitate. But a successful imitator is a much more obvious target. Instead of trying to select which spear works best, copy the spear of the most successful hunter; instead of trying to choose which shelter to imitate, copy the shelter of the healthiest family. By imitating the best imitators, the growth of memes finds a whole new gear.

The third step is where the question of genetic advantage begins to fade away, and where memes are gradually let off their leash: “selection for mating with the imitators”. Because imitation was an advantage to our ancestors who inherited the skill, they would also have been seen as genetically desirable; high-value sexual partners. They would have thrived when others did not, and so stood out from the crowd. By choosing a good imitator to mate with, you get close access to their imitation skills and all the benefits that come from them. Your children will also then benefit by inheriting these imitation skills in turn. Through generations of this selection pressure, crude and embryonic imitation becomes much more refined and effective.

The final step is a little predictable, but it is where that big brain of ours finds its explanation: “sexual selection for imitation”. Think of the peacock and its ridiculous tail feathers. These feathers are used for attracting female peahens, and nothing else. But the peahens are attracted to them. The bigger and brighter the tail, the more attractive the male peacock is to potential mates. So peacocks with ever larger and ever brighter feathers have more sexual opportunities, have more offspring, and those offspring (the male ones) will have similarly ridiculous tail feathers. The feathers are cumbersome, making their hosts easier targets for predators, but that one advantage of sexual selection is enough for the feathers to continue growing and to continue sparkling. This is called a “runaway sexual selection” and it should sound familiar.

As mentioned, the ability to imitate is not an easy task. It requires a lot from our biology, specifically it requires a lot of brain power. And also as mentioned, memes are great at exploiting sexual selection. If the selection pressure for the peahens was something like ‘mate with the peacock with the grandest tail feathers’, then the selection pressure for early human beings (and all human beings since) was probably something like “mate with the man with the most memes”. And just as with those tail feathers, before long this one characteristic (imitation) begins to dominate all others in terms of genetic reproduction. Our brains grow to accommodate more memes and better replication, those memes and that imitation are then sexually selected for, our brains continue to grow in order to handle more memes and better selection, and we end up with huge, cumbersome brains, as a case of “runaway sexual selection”.

Back to language. Again, without rehashing the whole space of socio-biological theories about how language evolved and its impact on our intelligence and species-wide success, memetics has a better answer (without the inconsistencies) and a different approach (one that encompasses and explains all those other theories). The difference between a silent person and a talkative one, is that the talkative one is likely to be a much better spreader of memes. So from a basic starting point, language is a tool for our memes. The only thing that memes want to do (again the wrong word) is replicate, and when we start to think about language in this way, aspects of it begin to make more sense.

Imagine you have heard some juicy gossip. The choice to tell someone or not, often doesn’t feel like a choice at all. Your biology seems to be firing against you, demanding that you repeat the words you just heard. If not gossip, then some current event you saw in the news. Some new movie you saw and liked. Or, of course, the clearest example of that hilarious joke you just listened to. It is easy to dream-up alternative theories about the origins of language, but much harder to find a theory that accounts for the fact that we are often overwhelmed by the compulsion to talk. Stick someone alone in solitary confinement, and they will soon begin having conversations with themselves. Tell someone else that you have booked them a week-long stay at a silent retreat, and watch them sink with dread before your eyes.

People who hold the meme for talking, will spread more memes; it is much easier to tell someone something than to act it out silently. And people who hold the meme for talking compulsively will have more opportunities, and wider audiences, to continue spreading their memes to. And in this way, as with our big brains and imitation, the meme pool begins to change the gene pool through sexual selection. So the question ‘why do we talk so much?’ has a nice, clean, encompassing, and deeply-explanatory answer: “We are driven to talk by our memes.”

The final ribbon on this theory of language sits in the details of its evolution. Look around and listen to the words we use, the phrases and sentences and paragraphs and conversations and debates and expressions, and what should hit you first is how innate it all is. There are differences, gaps, and outliers, but on the whole almost everyone you see using language, uses it as grammatically well as anyone else. And yet none of us learn language by being taught its structure, being corrected for our mistaken usage, nor even (and this is important) by “slavishly copying what they hear.” The grammar we study in school is but a tiny part of the natural structure (grammar) of language.

There was once a famous chimpanzee named Washoe, and an even more famous gorilla named Koko. They were famous because they could speak – well, they could use basic sign language. Having been taught a few key words, Washoe and Koko would build short – “three word” – sentences, requesting certain things, and even expressing themselves. Then after the “excitement and wild claims” had faded slightly, psychologists, linguists and native deaf signers, began to offer some doubt. The primates weren’t actually signing anything close to what language is. There was no structure, no grammar, no order to things, no understanding of what they were doing. Washoe and Koko had simply learnt a few symbols (they had to be trained and coerced), and were using those symbols to request things.

Young children on the other hand, do something extraordinary. Without too much effort they seem to absorb the language they hear, and the rules for its use. It is largely inexplicit. They often don’t even realise that they are learning or improving upon what they have already learnt, and yet without the need for reward or punishment, they pick it up and use it; in all its complexity and depth and structure. “The human capacity for language is unique.”

How this unique ability evolved is a tricky enough question, if for no other reason than languages don’t leave behind happy accidents in the fossil record. Archaeologists can’t go digging around in the mud for clues in the same way as they can for tools or bones. Extinct languages are lost, forever! There are clues – like the discoveries of art, burial rites, tool making, and trades – but they are distant and weak. The idea being that for such things to happen, language would had to have been on the scene. This is really just an argument that language would make such things so much easier, and so we are guessing that it might have been present. Not a convincing theory! Especially when language and thinking are so deeply wrapped together, it is almost impossible to speculate what might be possible without language.

Those big brains likely had something to do with it, but this misses the biological complexity of speech. A delicate and accurate control of breathing is needed, requiring the development of specific muscles in – and around – the chest and diaphragm. And the interplay between them is vital, overriding the mechanism of one in favour of the other, at just the right moments and in appropriate ways; allowing us to talk and breathe and function. We also need a wide variety of sounds, sounds that are distinct enough to convey the clear meaning of words. For this, our larynx is considerably lower than it is in other primates. But muscles and larynxes don’t fossilise either. Digging through what we know of our deep ancestors may never take us to the origins of language, but an easier answer might come our way if instead we simply “knew what language was for.”

A good replicator needs three things: Fidelity, fecundity, longevity. Let’s start with the second. In a world where genes have evolved creatures (ourselves) who are capable of passing on memes, how wide and how far those memes spread is an obvious challenge. For a meme to replicate it needs other hosts (people) to copy into, and who can then continue spreading it. The need is always for more hosts. And language becomes an extraordinary tool in this, allowing you to pass on the meme to large crowds all at once, even if none of them are even looking at you. Instead of using signs and gestures, speech allows memes to continue replicating, be it face to face, face to faces, or in the dark, or around corners, or over reasonable distances.

Fidelity. How does language help to improve the accuracy of what is being copied? This is fairly straightforward. Think back to Washoe and Koko, imagine they are together in a room and one of them has a primitive sort of meme running through their mind. The work that meme has to do in order to be replicated in the other, involves some heavy lifting. Signs can be ambiguous, gestures need to be deciphered, and behaviour is a mess of movement and sound: finding the one thing to copy (the meme) through the background corruption and superfluous activity is no easy process. Now add language, and everything becomes clearer. The meme can be communicated with much more accuracy, and in the event that the wrong thing is still copied, it is as easily corrected as saying don’t copy that! Copy this!

So what about longevity? It would appear at a glance that the problem of life-extension for memes is a problem of memory capacity. Someone communicates a meme to you, it is then stored in your brain until you can communicate it to someone else. If the meme is hard to remember, it might be partially forgotten, or lost entirely. Here language comes to the rescue. If you hear a series of random numbers or words or sounds and are asked to repeat them back a few minutes later, you will find it very hard to do so. If you are read a simple sentence on the other hand, remembering it will be a much easier task. Language adds structure and meaning to the sounds we hear, and this makes it considerably more memorable.

Besides, language doesn’t need to be repeated in an exact replica to convey the same meaning. If we are hunter-gatherers and I say something useful to you (a meme) like don’t go up that mountain because there are lots of dangerous bears, the message you pass on to someone else might be there are hungry bears on that hill, stay away, or scary animals live on those slopes, avoid them. There would be countless ways to express the same meme, and for this we have language to thank. It doesn’t take much imagination: think of a group of people who tend to copy each other. Now add language. Are they better or worse at copying? The evolution of memes explains the evolution of language.

So with all these memes running through us, and with all these changes that memes have made to our genetic code and our behaviour, what are we? We are all, down to the man or woman or child, gigantic memeplexes that bundle together in such a way that makes it all feel complete and singular. It makes us feel as a self! Blackmore calls this the selfplex – that constant, nagging feeling that ‘I’ am somewhere behind the rest of the human show. Perhaps it is better said in the title of her book: we are meme machines, and so if we ever want to understand who we are, to be happier, healthier, smarter, more productive, or more relaxed (insert whatever progress means to you), then we had better begin to understand our memes.

If you feel like you understand memes now, but are still oddly confused, that makes sense. Those early listeners to Darwin’s theory of evolution also understood the plain meaning of the words he spoke, but were also confused about the weight and inferences they carried; as was he. And make no mistake, Blackmore’s theory, with a few tweaks here and there, has the same astonishing explanatory value of Darwin’s, and the same world-shifting implications.

There are two ways to look at the path forward. We can do as Dawkins hoped, and begin to fight against our memes: “we alone on earth, can rebel against the tyranny of the selfish replicators”. Or we can follow Blackmore’s suggestion and discover that we are “truly free – not because we can rebel against the tyranny of the selfish replicators but because we know that there is no one to rebel”. Either way, it is worth seeking them out, looking into yourself, searching for the things you think and do compulsively, the things in your life that feel like they are stuck on repeat, the things that seem to have more control over you than you do over them. Not all our memes are good or valuable or worth having, many are downright harmful, and they can, by some effort, be de-weeded from your memeplex.

This is about three times as long as any article I wanted to write in this series. And I am tempted to say that this is a matter of how much this book, and how much this theory, meant to me. And I admit that I am captivated. And I really do think that Blackmore is onto something huge here. And I am sure that if we only understand our memes better, we can understand ourselves better and improve our lives. But if I am going to accept the theory, then I need to do a better job of thinking in terms of the theory. It would be more accurate to say that I have been infected by the meme of memes. Now let’s see if I am a good carrier or a good host or a good vehicle. “The driving force behind everything that happens is replicator power”, so the judgement of my success or failure will come down to whether or not I have managed to – in some small way – also infect you with this meme of memes.

*** The Popperian Podcast #20 – Susan Blackmore – ‘Memes - Rational, Irrational, Anti-Rational’ The Popperian Podcast: The Popperian Podcast #20 – Susan Blackmore – ‘Memes - Rational, Irrational, Anti-Rational’ (libsyn.com)