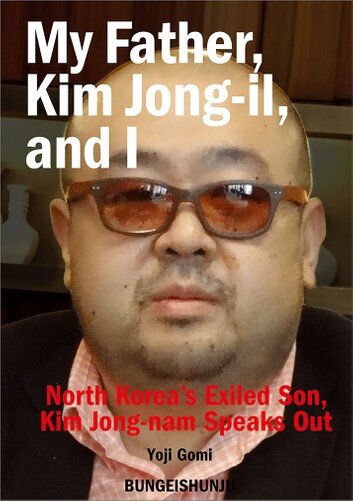

It was early May, 2001, and a paunchy man with a delicate manicure was struggling off a flight at Japan’s Narita Airport. His wife and children – less fleshy, less plump – followed impatiently behind him. All four were travelling under Chinese aliases on forged Dominican Republic passports. Sweating in the early summer heat, and wearing pink-tinted sunglasses, the man sat, exhausted, waiting for his designer luggage to hit the carousel.

None of them made it through immigration, and all were deported back to China after three days of arrest. Pleading for the Japanese authorities to change their minds, the man tried to win them over with honesty, saying that he just “wanted to go to Disneyland”. In those three helpless days, global media attention began to crackle into life – this was no ordinary family vacation.

The next time the world would hear about Kim Jong-nam in such detail – and with such interest – was at another airport, this time in Malaysia. He was collapsed on a stretcher, and choking to death from the nerve agent that had been smeared across his face – assassinated as a public spectacle by his younger brother, and usurper to the North Korean throne, Kim Jong-un.

Sticking to this theme, My Father, Kim Jong Il, and I is the story of yet another airport, and a different luggage carousel – just as ill-fated, just as overweening and tragic. This time it was Beijing International Airport, and the man stalking-up behind Jong-Nam – and who would soon be lecherously drawing his blood – was Japanese journalist, Yoji Gomi.

Recognising Jong-nam from the “plump neck” and “number of moles” on his face, Gomi “followed him… outside of the airport building, and kept asking questions”. When Chinese officials ushered Jong-nam into a waiting taxi, Gomi pushed forward through the car’s open window with “my business card containing my email address”; regretting only that he hadn’t called the next taxi and “followed him from the airport.”

Within a country like North Korea, it is hard to feel sorry for someone who grows up well-fed, comfortable, and dressed in gold jewellery, but in these pages Kim Jong-nam is a man falling apart, lost, isolated, and so lonely that even the offer of exploitation from a complete stranger sounds appealing. If the question ever needed answering, then here it is: Yes! It is possible to be so in need of a human touch that even being strangled has its charms.

The old adage, ‘never trust a journalist’, doesn’t do any justice to what happens in My Father, Kim Jong Il, and I. This is far more abusive, and far more ethically unmoored, than what most people reasonably imagine by that phrase.

As soon as Jong-nam sends a first lonely email to Gomi, a whirlwind of tradecraft kicks into gear, every emotional trigger is pulled, every angle gets tested, and information is slowly drained from Jong-nam despite his best efforts and attempts to define the relationship on his own terms. It plays out like a man being dragged slowly into ever deeper water, and then drowned before indifferent eyes.

The language is always brotherly, familiar, and digging for emotional debt – “heartfelt condolences”, “my deepest sympathy”, “your dear mother”, “take care of your health”. Noticeable (perhaps even to Jong-nam as well), the aim here is to guilt Jong-nam through kindness into revealing and commenting on what he doesn’t want to, or what he is rightly too scared to.

Jong-nam is always yammering away with unconscious delight, and then quickly walking back his words; recognising too late the danger he might be in each time. And knowing where this all eventually ends for him, it becomes a little hard not to read it without anger. Especially when Gomi doesn’t seem to appreciate, or perhaps care, about the risks he is asking his pen pal to take.

Even after being told by Jong-nam that a private threat was delivered to him from Pyongyang – “I received a sort of warning from them” – and that the regime were not only upset about what Gomi had been publishing in his newspaper about their discussions, but that it was also likely that their “email exchanges were being monitored”, this still isn’t enough to let caution win the day.

Email silences are met with fawning concern, and being told that a topic is off-limits simply translates to Gomi’s ears that such inquiries should be delayed, or asked about in roundabout ways, after some sweet talk. Ordinary alarm bells and sensible etiquette never enter the scene here, because as Gomi tells us, “I was growing anxious for a reunion with him”, as if Jong-nam were a long-lost friend.

This is, of course, Gomi’s job. But it doesn’t make the whole process feel any less dirty. Especially when the glee in the journalist’s eye is obvious at every turn, bragging at length about the number of emails they exchanged (“no other journalist has been lucky enough to have exchanged more than 150 emails with him”), the handful of face-to-face meetings, and constantly reminding us that “I might be the journalist who has had the deepest exchanges with him”. This is less of a book than a glorification of a rare and lucky scoop.

And to make it all seem a little more gallant and noble, Gomi elevates Jong-nam inappropriately, with too much self-agency and intelligence – “He is a voracious reader of books”, “He analyses the situation of his mother country very coolly and objectively”, “he is frequently layering his wording with implicit meaning”. Gomi wants you to believe that Jong-nam is “a broad-minded man”, so that his book is seen as less an event of callus manipulation, and more of a complex chess match between geniuses.

Which belies the trivial, postcard-like tone of most of the emails – “Beijing is quite festive right now” – as they circle slowly toward dangerous questions about North Korea. It’s the foreplay and emotional groundwork of a Nigerian email scammer talking his way into your trust and closer to your bank details.

But all the shading in the world can’t disguise the horrible profiteering that is playing out before the reader. As Jong-nam rattles on about his childhood, it becomes apparent that this is, more than anything, an unintended study in loneliness. Jong-nam’s stories quickly repeat and contradict, and when he does offer some criticism of North Korea there is never any substance to it.

The questions bounce off him like an undergraduate trying to bluff their way through an oral exam. He is angry about the economy and wishes it would liberalise, but offers no details or thoughts that he couldn’t have read in a Chinese newspaper. He is angry about the succession of his brother, but focusses on Jong-un’s age and experience a little too much. There is no inside track on the North Korean royal court here, just a shallow and embittered man, jealous at being passed-over.

You can only talk about the same things so many times, before it becomes obvious that you have nothing new to say. And it all makes sense. After decades in exile, it would be surprising if Jong-nam still had some secrets hidden away, or if those secrets still held any relevance to the North Korea of today.

There is nothing here, no scoop, nothing to report, only the image of Jong-nam – a minor celebrity squatting in the casinos of Macau, unmoored from family, home and influence – looking to milk his last claim to fame. And it’s also here, clumsy, buffoonish, and drawn in simple colours, that Kim Jong-nam should now be understood – not through the light that Yoji Gomi wants us to re-imagine him in, and not through the soiled pages of My Father, Kim Jong Il, and I.

In that Japanese airport, as he begged in a “high-pitched voice” to be allowed to visit Disneyland, the immigration officers must have first laughed, and then felt a little sympathy, at the artless, childish nature of the fraud before them: the fake name on Kim Jong-nam’s passport, the name that he had chosen for himself in Chinese characters, was “The Fat Bear”.