Democracy matters – we can all feel it in our bones. There is something emotionally satisfying about being able to hire and fire your government, to stand in judgement over how your society is run. And by handing this authority to the masses, it is denied to the oligarchs, the aristocrats and the dictators. Yet despite all these things having a recognisable value, even thinking in this way is a grave mistake. The problem that democracy solves has nothing to do with rights, freedoms or even ensuring that the best possible leaders get into power. In some ways these come along for the ride, but democracy has only one significant advantage worth caring about – error-correction.

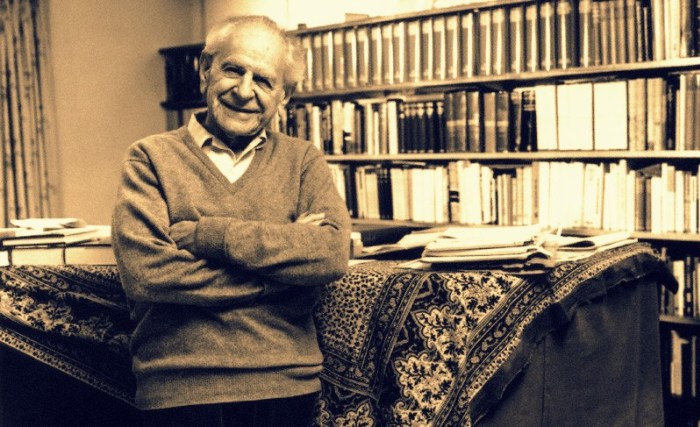

Just as it goes with knowledge creation, we cannot predict the future – and so the natural state of things is error. We are all wrong, incompetent, flawed and prejudicial in ways we don’t properly appreciate, all the time. This, of course, also applies to our political leaders, and to our ability to select those leaders. The hope of choosing “The Best” people – as Plato put it – to govern society is misplaced, as is the underlying question – also Plato’s – of “who should rule?”. Karl Popper’s solution to this might have felt like an easy fix, but it was also the most important development in political philosophy that had ever occurred. He did so by embracing the fact that mistakes are everywhere, and then turning the question around, asking instead ‘how do we best remove bad leaders without violence?’

From this we get democracy, but only in concept – it is the best system we have available to us for error-correcting bad leaders and bad policies. Yet this only takes us so far, in fact it leaves most of our work still ahead of us. The limitations we see in our democratic systems often come back to the fortuitous, yet tragic, fact that we historically found our way to democracy not through Popper, but through Plato – with the wrong question still in mind. Free of this, and with Popper’s criterion, it is possible to tune-up and improve upon our democratic institutions – to solve problems of disproportionate political power, and achieve arithmetic fairness. The ‘Open Society’ is still, and always will be, within our reach; we just have a slightly different question to ask now – ‘what kind of democracy is most effective at removing bad leaders and correcting bad policies?’

The dismissal of a government by regular voting, is a robust form of ensuring that leaders are always accountable, and of avoiding anti-democratic takeovers. But we never actually rule ourselves – on election day the keys of government are always handed over to our political leaders, after which we sit and hope that they are returned to us at the appropriate time. And when it comes to the bureaucracy – the people in charge of implementation, of minor decisions, and whose information and advice politicians rely upon – we often don’t have any mechanism to change them at all (barring malpractice of some variety).

And yet when you start with Popper and not Plato, everything simplifies. We don’t need to edge delicately into this imperfect space, but rather go straight for the jugular of democratic change – voting systems. The idea behind democracy that we instinctively hold, is that parliament should be a representation of the people – each individual member a mirror for their constituency; the nation in a microcosm. As closely as seats in parliament can be matched numerically to the views of the people voting, the closer a society is to the best democratic system… or so the theory goes. This is called proportional representation, and it is a terrible mistake.

Proportional representation favours parties and not people, with citizens tending to vote for what they most clearly recognise and understand – political parties – and it is those parties that select who should represent which constituencies. And what is the purpose in setting up a political party other than to further an ideology – policies may change, but their founding principles rarely do, lest they risk losing their established supporter base. This becomes a shield against error-correction and a system designed for personal advancement. The people who most adhere to the core ideology are shuffled into safe seats and conferred with significant campaign financing, while voices to the contrary (error-correction) are filtered out the other direction.

Elected representatives in this system owe their allegiances much more so to the party that supports them, than to the people who voted for them. A candidate that is elected under the banner of one political party and then later defects to a different party, or to sit as an independent, is often considered to be betraying his/her constituency – because they likely gave their votes only in consideration of the party’s platform, and not with the individual candidate.

This doesn’t just rob the voters of choice (the possibility of error-correction), but also robs the elected individual – and the political system as a whole – of personal responsibility between political leaders and the voting public. With this aspect built into its fabric, proportional representation tends to also cause a proliferation of political parties – and though increased choice seems to come with this, it presents a significant roadblock against the removal of bad leaders.

The more proportionate the political system, the more power that is afforded to smaller parties and independent members of parliament. In any given single electorate it is increasingly rare that one candidate will secure the votes of more than fifty percent of the population. Trying to match these numbers to elected members, a proportionate voting system tends toward ensuring that no political party holds a majority of seats in parliament. When seats in parliament successfully mirror the broader societal breakdown in this way, the means by which governments form, or fail to do so, is through coalition – and in coalition the desired fairness breaks down, from the opposite direction.

By forming government through proportional representation, the smaller coalition parties are –perhaps counterintuitively – afforded disproportionate political power. With no major party holding a majority of seats, and therefore needing the support of minor parties to form government, it means those minor parties effectively get to choose the government and to choose who becomes Prime Minister. And, of course, they are likely to make this decision in their own political interests. Rather than weighing the merits of each major party, or even leaning toward the party that has achieved the most votes, they will seek to make conditions upon their support and smuggle their own policies into power.

The fear of having unpopular political decisions legislated through the backdoor in this way, has often led to a renewed support for either of the two major parties. The thinking runs: if your political views best align with a minor party, then you should instead vote for the major party that most closely (though less perfectly) matches-up with you – anything else might risk overt minority party control, and not necessarily from the minor party that you support.

But this still doesn’t protect against bad policies in the way that people hope – a greater majority for the two major parties doesn’t do much to change the calculation here. If they both increase their votes equally, then they will stand as counterweights, and the role of selecting government will still be returned to the minor parties, unaffected by their diminished votes. The price of gaining power is unchanged. (The only challenge to this being that if minority party votes shrink dramatically, then maybe a major party could achieve government in their own right. This is a possibility, but a decreasingly likely one based on the range of views and the range of parties now operating in many democracies).

This bores the inevitability of coalition government into the foundations of most modern democracies – and with it the fragility of that government, both in its formation, and also its sustainability. Worse, by producing coalition governments, proportional representation further reduces political responsibility by making decisions not only reducible to the party as a whole rather than to individual representatives, but also reducible to the collective decisions and policies of multiple parties, in arbitrary coalition.

With an understanding that no party will likely achieve a majority, voters are stuck when it comes to Popper’s criterion of seeking to remove bad leaders as quickly and effectively as possible. By voting against an incumbent, you might inadvertently end up returning them to power if they cut a deal with the alternative that you voted for. Under a system like this, it becomes incredibly difficult to ever vote ‘against’ anyone, as opposed to ‘for’ a particular candidate – and so we are back with Plato, having made no progress and still trying to answer the wrong question. It becomes impossible to be decisive with one’s vote, and impossible to send a decisive message of judgement upon a government or set of policies. And this is witnessed today by the attitudes of political parties that suffer electoral setbacks, who more often than not see this as a natural fluctuation, rather than a firm and conscious indictment upon their failures.

Proportional voting systems allow for very bad governments to remain in power in the face of very good oppositions, so long as they can wheel-and-deal for minority support with greater success. For many the solution to this has been preferential voting, whereby people don’t just vote for a single candidate, but also select second, third and fourth choice options in the event that their first choice doesn’t manage to secure over fifty percent in the original round of voting. The hope here, is that by selecting a list of candidates it becomes more likely that better leaders gain power. But of course, this is the wrong question. What we want to do is remove bad leaders, not elect good ones.

In some ways the preferential voting system does this. If the vote in any given electorate is split between various parties, and yet there is a consensus that the incumbent member is a bad leader, the divergent voting patterns might still end up removing them from power by a majority of voters placing that incumbent last on their preference list. There is scope here to remove bad leaders despite no party receiving a majority of votes.

This is something, but it is still a narrow and constrained form of error-correction. The removal of any individual, poorly performing, Member of Parliament is good, but it doesn’t limit the problem of disproportionate minority party control at the level that matters. Preferential systems do open up avenues for removing bad leaders, but they don’t address the issue of minority parties influencing the government through insisting on cabinet positions, the legislation of unpopular policies, and even the king-making ability to select who holds power. On the national scale, bad policies and bad governments are still increasingly immune from error-correction if they can secure third party support.

By entrenching minority rule, all such systems fall down badly. The only thing that the third largest party in any political system of this kind realistically fears is becoming the fourth largest party; not the electorate in any real sense. Minor parties need huge swings against them to ever force them out of power, and so major parties can also take more liberties with – and often outright ignore – the voters, under the knowledge that their success in achieving power hinges much more so on making deals with minor parties.

This is error-correction, but an incredibly parochial and poorly functioning variety. Government ends up being run from fringe ideas, politicians fall over themselves to please the views of minor, single electorates, and parties bargain their way into power instead of being elected. Even occasionally producing the absurd spectacle – and catastrophe for political accountability and representation – of just one individual in an entire country being able to make-and-break both governments and national policies. The hope of institutionalising error-correction, in its best form, dies here.

So what should be done – in what direction would Popper have us move? A return to something that feels a little archaic, and that appears to lack the arithmetic nuance of proportional voting systems. The two-party system is something designed to secure majority governments, and institutionalise not only accountability but also constant error-correction through criticism and comparison with an alternative government. It is a system that presents elected members with a simple proposition: perform well and in their electorates’ best interests, or be removed from power. There are no backdoors, no deals to be cut and no way of ignoring the will of the voters – they either succeed or fail on their own weight, and the intended reward or punishment is always delivered unambiguously.

In a first-past-the-post, two party political system of this kind, leaders and parties will hold higher degrees of power once elected – allowing manifestos and policies to be implemented without third party hindrance or the fudging of policies. This can then be tested in public view, and a clear option can then be presented to voters as to whether to stick with the policies or accept the criticism from the second major party and vote to change government. A dialectical process of constant policy conjecture, constant unfettered application of those policies, constant criticism, constant presentation of alternatives, and then constant clear and unequivocal electoral choice.

This is still less than perfect, and there is a risk in this system that the scope of possible error-correction – possible criticisms and alternative policies – will be limited in the absence of widespread minor parties. And there is also a feeling of suppression and disenfranchisement here by denying the space for minority parties to rise and/or major parties to fall. It can all begin to look a touch anti-democratic. But the reach of this fear isn’t quite as pernicious as it might feel – healthy debate and constant error-correction will occur inside the two major parties, and the changing of a party platform is likely to become quite drastic and radical after two or three electoral losses in a row, with the failure of each party laid bare by the fact that they are only one-of-two games in town, and this is likely to happen even in the absence of a significant or sustained defeat.

When a political system is thick with minor parties, adjustments of this kind are unlikely to ever happen, with change predominately coming about through the rise of new political parties; which even in the friendliest of conditions is not an easy thing to organise. Returning again to Popper’s criterion of being able to remove bad leaders most effectively, a well-functioning democracy doesn’t need a spread of voices (this will always likely occur) as much as it needs sensitivity to the wishes of the voters, policy flexibility to match that sensitivity, and the healthy development of ideas followed by the healthy criticism of those ideas.

Just as with knowledge creation, we don’t – and never will – know the best possible political system; only ever approximations of it, that will then also require constant error-correction and improvement. It is a utopian fantasy to imagine that a government exists by some make-up of society that when voted for will not make mistakes, will not enforce bad policies, and who understand the future. Knowledge cannot exist in advance of problems, mistakes are the human condition, and any coalition-producing political system has the quality of making it harder to correct bad leaders and bad policies than it needs to be. All we can do is choose better-and-better political systems judged solely by their ability not to elect the best leaders, but to remove bad leaders as easily as possible without violence.

For Karl Popper this is the Open Society, and yet once here the risk of authoritarian relapse still exists, edging ever inwards in search of space and opportunity… Continued in part 3