It is something so instinctively true that it barely needs repeating – democracy matters because it is about freedom, rights and empowerment. It satisfies, as much as anything, an emotional need. And yet this is completely wrong! So much so, that thinking of this kind is in fact a pathway in the opposite direction – toward domination, disenfranchisement and totalitarianism.

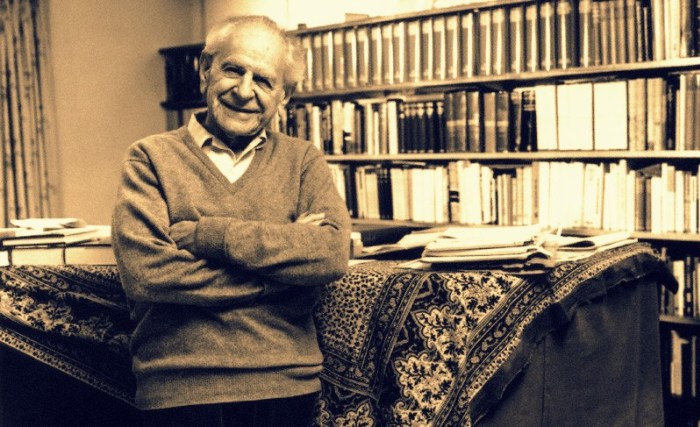

It is true that we should be able to elect and remove our political leaders, and yet by focussing on the hiring process we edge ourselves closer to tyranny – wilfully handing over the keys to our own society. Writing during the rise of Nazism, Karl Popper applied his “war effort” to understanding the psychology of totalitarianism. Where most people saw answers in biology or social conditioning, Popper instead found a technical – even mundane – sounding truth. It packaged up other such theories, simplified the whole process, and exposed the unlikely space that totalitarianism needs to survive. And having come so far, having embraced democracy so substantially today, it is a risk that we – often – no longer recognise.

The ability to elect our political leaders does nothing to ensure that those leaders won’t become tyrannical, or even that democracy will be a better functioning system than an authoritarian one. In fact it has almost become fashionable today for people to question the value of the democratic systems we live under, and to do so in comparison with the rise of seemingly cleaner, faster growing, and less problematic systems like that in China today. From all directions it feels like non-despotic, developmentally-focussed, authoritarian regimes like these are simply capable of things that democracies are not.

Sure, the trade-off is slightly unpleasant, but for many people it feels increasingly acceptable: the citizens have their voices marginalised or ignored, and in return unbelievably impressive things can be achieved. Without concern for civil liberties, crime can be addressed a lot more swiftly and comprehensively, limitations on development can be removed without fuss, and large-scale national policies can be introduced without regional pushback or legal challenges. The ability of the Chinese government to reach decisively into society, to mobilize people and resources, and to control the direction of change and progress so completely, feels not only like a good thing, but also exactly what most modern democracies are lacking.

Marred by political infighting, bogged down by the need for compromise, limited by parliamentary diversity, and constrained by the legal challenges of minor groups, democracy increasingly feels middling, messy and unproductive. So we get national, resigned-to-the-outcome mantras like ‘it doesn’t matter who you vote for, they are all the same’. Democracies just don’t feel designed for rapid progress, or even for passing good policies into law. And in the event that the stars do align in this regard, the next electoral cycle is always never too far away, and any good work can be undone by a new government, incentivised by the adversarial nature of our politics to roll back the changes even if they agree with the previous policies.

This stasis and inaction is most apparent when compared with Chinese style authoritarianism. Crackdowns like that in Tiananmen Square are unpleasant, and something most people would not like to see happen in their own country. But as a price to pay for a far superior political system, and the promise of noticeable improvements in their lives, those same people often become envious. It begins to look like a compromise worth making. And this is where the discussion ends, in a simple choice between a system that makes rapid progress, and a system that respects individual rights; of which the right to vote is one.

This is a completely false understanding of the value of democracy, and with it the limitations of authoritarianism. Democracy isn’t about electing the best leaders, it’s about removing bad ones as quickly, effectively and bloodlessly as possible. There is a historical element in our failure to understand Karl Popper here – and our failure to understand the origins of totalitarianism. The Chinese state represents a long tradition – not limited to any country or people – as universal as anything else we have.

Our first clearly recognisable attempt at an Enlightenment – ancient Athens – was not an attempt to keep things the same, but rather to open-up old ideas, values and institutions to criticism; and so with it bring about change. Socrates paid the ultimate price for this, famously put to death for the charge of ‘corrupting the youth’. Traumatised by this moment, yet also emboldened by his teacher’s courage, Plato internalised a reasonably sensible lesson. He sought to avoid these types of mistakes by devising a better, perfect society, governed by perfect leaders. As Plato saw Socrates’ death as a problem of who held power – in this case they weren’t the right people, and so they couldn’t see the mistake they were making. The idea of ruling by authority, or of deferring to traditions, wasn’t wrong in itself – it was only that they had the wrong authorities and wrong traditions.

And this instinct – now replicated in places like China – is understandable. It is a product of what Popper called the “strain of civilization” – the deep insecurity that comes from a rejection of tribalism (belonging) and the embrace of fallibilism. The idea that all authorities, regardless of their claims to knowledge, are hopelessly flawed (just like the rest of us) and so the only reasonable thing to do is to shake-off the claims of parent-figures, and to embrace a world whose natural state is error. It’s not easy. Personal responsibility and individual freedom are always inseparable from anxiety, fear and isolation. It is the shift away from the childlike impulse to find a protective and all-knowing parent. And for Popper, it is the choice between living in an ‘Open Society’ or a ‘Closed Society’.

And for all the well-meaning intentions of Plato, he couldn’t bring himself to make the adult choice. By dreaming up the perfect ‘Republic’, he was consciously creating a hierarchical order that could never be challenged, never be changed, and so had the same qualities of the system that he wanted to reform. Stuck on the question of “who should rule?”, he was – without realising it – simply trying to replace one tyranny with another. And this is where the arguments in favour of modern totalitarianisms, like that in China, begin to breakdown. The person willing to abrogate their rights in exchange for increased wealth, standards of living, and global power, is still making a mistake on those very grounds.

China has a one-party political system, and for the sake of argument let us afford those people at the top of the party (those people running the country) something that no leader ever deserves – good intentions. Let’s just say they aren’t in it for themselves, but only for the betterment of the Chinese nation – and that they accept the responsibility to rule only because they honestly see no one else who is better qualified. They see themselves as best fitting Plato’s criterion for government – they are the best people for the job. And from their position they probably feel this is true, which again runs us a little closer to the real issue here.

The protestors in Tiananmen Square thirty years ago were fighting against corruption and for democracy, yet what they were really doing was something a lot simpler – they were offering criticism. There were certain things about Chinese society – foremost their lack of a say in how they were being governed – that they disagreed with. And they chose to protest in the manner they did, only because they didn’t have any other forum under which to try and correct the errors they believed they had found. However, the Chinese government saw only a break in social harmony, a risk to economic growth, and the feeling of history repeating itself and their country collapsing back into internal conflict and maybe even civil war. It’s the same impulse that Plato had when he wrote that social justice “is nothing but health, unity and stability of the collective body”.

Individuals on the streets, blockading public areas, and disrupting everyday life, can certainly have an unpleasant feel about it. Anyone that disagrees with the purpose of their protest is also likely to resent the imposition. The decision made by the Chinese government on June 4th in Tiananmen Square was misunderstood by those on both ends of it. The values underlying it – the desire for a direct political voice vs. the desire to maintain harmony at all costs – obscured what was actually happening. It sounded again like a question of ‘who should rule?’, but it was a plain – even mundane – attempt to error-correct mistakes. And whether it is Plato in Athens or Deng Xiaoping in China, the rejection of avenues to error-correction has implications far beyond any individual event.

Both Plato’s ‘Republic’ and modern day China are examples of Closed Societies – and both charge forward toward the same strange and impossible place – the idea that tomorrow’s knowledge can be known today. To reject ideas as wrong – which happens every day in democracies around the world – is a completely different behaviour from that of stopping new ideas from ever bubbling-up, from ever being voiced let alone heard, and from the impact of those ideas ever being felt. The latter might feel cleaner, more efficient, and even more appropriate if the ideas in question appear ridiculous, but what is being lost is more than messiness – it is also the only means by which we can actually improve things.

Authoritarianism is a surrender of the individual – the interests of any one person in favour of the interests of the state. The sacrifice in lives and suffering under the crackdown at Tiananmen was easily justified under the shadow of China’s collective strength and prosperity. This is a hallmark of all authoritarianisms – it comes in different forms, in different justifications, and with different ‘higher’ principles, but the individual is always expendable when compared to the state. This is not just possible to accept, but even axiomatic, once a certain conception of history becomes mainstream truth. That is, the flow of history is governed by predictable laws, that these laws are easily comprehensible, and that they point in a clear direction; an end-game. This is ‘Historicism’, and the mistake that Popper saw in it, that so many people seemed to have strangely missed – or naively bought into – was not just the claim that the truth is manifest, but that the future is also predictable.

Plato built his Republic on this foundation, as did almost every other political philosopher that came after him. Whether it was based on aristocratic order, divine rule, race-based nationalism, or workers seizing the means of production, all these visions involved focussing on a small set of known problems and then imagining that their resolution would be the last ones ever needed. There simply wouldn’t be any more problems, or that any future problems would be parochial matters; tinkering on the fringes. In short, they were all utopian. Before the full horrors of Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union were widely known, Popper knew what they would be. Systems which elevate the collective above the individual, that censor criticism, that centralise control, and that impose rigid hierarchies, are systems predisposed to tyranny and horror.

Which brings us back to those moments in Tiananmen, and the apparent successes of Chinese authoritarianism. Many critics saw the crackdown as a sign of a deeper illness, something that might not kill its host right away, but that in time, inexorably, would do so. The hope they shared was that political defiance – no matter how ineffectual it might feel at the time – will slowly shift people’s perceptions, further unrest will grow, and eventually it all snowballs into political overthrow.

Though coming from a different direction, there is a touch of Historicism about this type of thinking too. All questions of inevitability are fallacies. The sickness in the Chinese model has nothing to do with their ability – or lack thereof – to control future dissent, but rather the lack of error-correction that they are allowing into their political decision-making. By creating a system that supersedes the individual, China – and other authoritarianisms – are claiming an immunity to error; or that it is enough for the select few people in positions of power to error-correct each other, in house.

Popper showed that all knowledge is conjectural. It doesn’t come to us through the senses, and our experiences of the world around us don’t reveal true theories; instead everything is theory laden. The fact that we can ever know anything is only by an uncertain method of proposing theories (educated guesses), and then testing those theories against criticism – conjecture and refutation. At the point when a theory survives exposure to the best available criticism, we don’t adopt it as true, we only don’t reject it as false; always leaving open the possibility that future criticisms – which we can’t conceive of today – might force us to abandon it altogether.

Being wrong is the natural state of things, and no truth can ever be so incontrovertible that it should be walled-off from criticism. To do so, is to claim an understanding of what is not available to anyone – the future growth of knowledge. Truth and progress only come about through the open challenge of one set of ideas by another – bad ideas are destroyed by this process, and good ones are strengthened.

Popper matched his political theory to this theory of knowledge. Instead of reaching too far, and imposing too many values that might be hard to challenge or change, democracy should be minimalist – designed to do nothing more than fix mistakes by removing bad leaders and bad policies quickly, and without violence. And constitutions – or any other means of defending the value of democracy – should simply “make anti-democratic experiences too costly for those who try them: much more costly than a democratic compromise”.

By silencing the protestors at Tiananmen, and anyone else that has tried to follow their example, China is closing itself off to a broader range of ideas, a broader range of criticism for existing ideas, and a broader means of error-correction. The limited range of error-correction happening inside the Chinese Communist Party today might have been sufficient to transform China into a global power, but that is only because there are greater levels of error-correction there now (though still limited) than existed under the shadow of Mao Zedong. The Great Leap Forward was a mistaken policy,; what turned it into a human catastrophe was a fear of criticising it as a policy, and the silencing of those people who dared to do so.

The correction of mistakes is the only means of making progress that we have available to us. By limiting this into the hands of a select few people, China was also limiting its ability to respond to failures, to make changes, and to improve things. If it wasn’t the Great Leap Forward, it was the Cultural Revolution, if not the Cultural Revolution then it would have been something else. China today is no longer making this same level of mistake simply because it has allowed more criticism than it did previously.

Yet by still limiting this range of criticism to those select few people in the upper hierarchy of the Communist Party, China continues to expose itself to unnecessary levels of mistakes. They are unlikely to be as obvious as the calamities of the past, but they are happening, and they will continue to do so. And this doesn’t just relate to the creation of bad policies, but also a sluggishness in recognising them as bad, and then the failure to replace them with something better; again as quickly as possible. If we are being generous with the number of people in the elite circles of the Chinese Communist Party holding any real power, we might accept a figure of about a thousand – and a thousand-odd people doing error correction is just not as good as what could be nearly a billion in a Chinese democracy. A billion people looking for errors in their society, a billion people suggesting alternatives, and a billion people constantly – and loudly – judging policy outcomes.

Democracy is messy, annoying and frustrating, but only because knowledge creation is also. Anyone, or any government, claiming to be an authority, to be beyond criticism, or claiming that any given truth is self-evident (that they know it for certain) is simply making the same mistake that doomed almost every human society that has ever existed. They are always on the edge of something unpleasant, of a new Great Leap Forward, or of something much worse. Countries like China may look prosperous, successful, or even worth emulating, but they are exposed to catastrophe and limited in their ability to make progress in a way that no democracy is.

And that limitation is not just political, or technical, but moral as well… Continued in part 4